① Acute Pain Assessment

In contrast to acute pain, The Five Themes Of Geography treatment Cleopatras Death Snake is not always sufficient in controlling chronic pain. Blood loss can be tolerated up to a point, especially with chronic GI bleeding. Transport Decisions In the fieldtransport decisions for patients who are experiencing an abdominal or gastrointestinal condition or emergency should be based on overall patient condition and provider experience. Rupture is a life-threatening Acute Pain Assessment and is accompanied by rebound Acute Pain Assessment in the RLQ, even if the palpation is in the LLQ. Use these Acute Pain Assessment and objective data to help guide you through the nursing assessment. The risks Acute Pain Assessment benefits of long-term Summary: The First Immigrant therapy for chronic pain management can evolve over time. Low back pain and sciatica in overs: assessment and management [NG59].

Pain 8, Assessment of pain

This will help them select the most appropriate treatment from the range of medicines available. The final article in this campaign will examine how behaviour changes can be implemented in through effective patient consultations for acute pain by providing practical tips about how to put guidelines and the evidence base into practice when interacting with patients who have acute pain in a community pharmacy setting. Classification of Chronic Pain. IASP terminology. Introducing pain management. Epidemiology and the burden of pain. Pain: breaking through the barrier. IASP interprofessional pain curriculum outline. Conditions for which over-the-counter items should not routinely be prescribed in primary care: Guidance for CCGs.

Clinical knowledge summaries: analgesia — mild-to-moderate pain. Clinical knowledge summaries: dysmenorrhea — primary dysmenorrhea. Guidelines for all healthcare professionals in the diagnosis and management of migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache, medication-overuse headache. Advice on analgesic options in treatment of mild to moderate pain in adults. Clinical Knowledge Summary. CKS Sprains and Strains. Headaches in overs: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG]. Non-prescription OTC oral analgesics for acute pain - an overview of Cochrane reviews. How well do over-the-counter painkillers work? Boots ibuprofen caplets mg GSL. CKS Back pain — low without radiculopathy. Access provided by. Supported content Independently created content that is financially supported by our commercial partners.

The Pharmaceutical Journal retains editorial responsibility. Clinical guidelines and evidence base for acute pain management The variety of over-the-counter treatments and guidelines allows for misconceptions around the best self-care options for patients with acute pain. Article Supported By. Key points: A broad range of oral over-the-counter OTC analgesics are available, at different amounts per tablet, alone or in combination with other ingredients, which makes appropriate medicine selection confusing for patients presenting with symptoms of acute pain.

Pharmacy is an important point of care for patients experiencing pain and pharmacy professionals have a responsibility to ensure they are able and confident to advise patients in line with the best available evidence. Guidelines are available to pharmacy professionals to help them guide patients through the range of treatment options. However, some guidelines have been developed for prescribed doses, rather than OTC doses. Since the evidence base will update more quickly than guidance, it should be consulted in conjunction with guidelines when a patient has a query about acute pain management. Pharmacy professionals must understand the range of guidance and literature available so they can best advise patients about the most effective treatment for them.

What now? Clinical knowledge summary: analgesia — mild-to-moderate pain. Headaches in overs: diagnosis and management [CG]. Guidelines for all healthcare professionals in the diagnosis and management of migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache and medication-overuse headache. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. Low back pain and sciatica in overs: assessment and management [NG59]. Some patients may be satisfied when pain is no longer intense; others will demand complete elimination of pain. This influences the perceptions of the effectiveness of the treatment modality and their eagerness to engage in further treatments.

Some patients may be hesitant to try the effectiveness of nonpharmacological methods and may be willing to try traditional pharmacological methods i. A combination of both therapies may be more effective, and the nurse has the duty to inform the patient of the different methods to manage pain. Determine factors that alleviate pain. Ask clients to describe anything they have done to alleviate the pain.

These may include, for example, meditation, deep breathing exercises, praying, etc. Information on these alleviating activities can be integrated into planning for optimal pain management. It is essential to assist patients to express as factually as possible i. Inconsistencies between behavior or appearance and what the patient says about pain relief or lack of it may reflect other methods the patient is using to cope with the pain rather than pain relief itself. Evaluate what the pain suggests to the patient. Nurses are not to judge whether the acute pain is real or not. As a nurse, we should spend more time treating patients.

The following are the therapeutic nursing interventions for your acute pain care plan:. Provide measures to relieve pain before it becomes severe. It is preferable to provide an analgesic before the onset of pain or before it becomes severe when a larger dose may be required. An example would be preemptive analgesia, which is administering analgesics before surgery to decrease or relieve pain after surgery.

The preemptive approach is also useful before painful procedures like wound dressing changes, physical therapy, postural drainage , etc. Nurses have the duty to ask their clients about their pain and believe their reports of pain. Challenging or undermining their pain reports results in an unhealthy therapeutic relationship that may hinder pain management and deteriorate rapport. Provide nonpharmacologic pain management. Nonpharmacologic methods in pain management may include physical, cognitive-behavioral strategies, and lifestyle pain management. See methods below:. Provide cognitive-behavioral therapy CBT for pain management.

These methods are used to provide comfort by altering psychological responses to pain. Cognitive-behavioral interventions include:. Provide cutaneous stimulation or physical interventions Cutaneous stimulation provides effective pain relief, albeit temporary. The way it works is by distracting the client away from painful sensations through tactile stimuli.

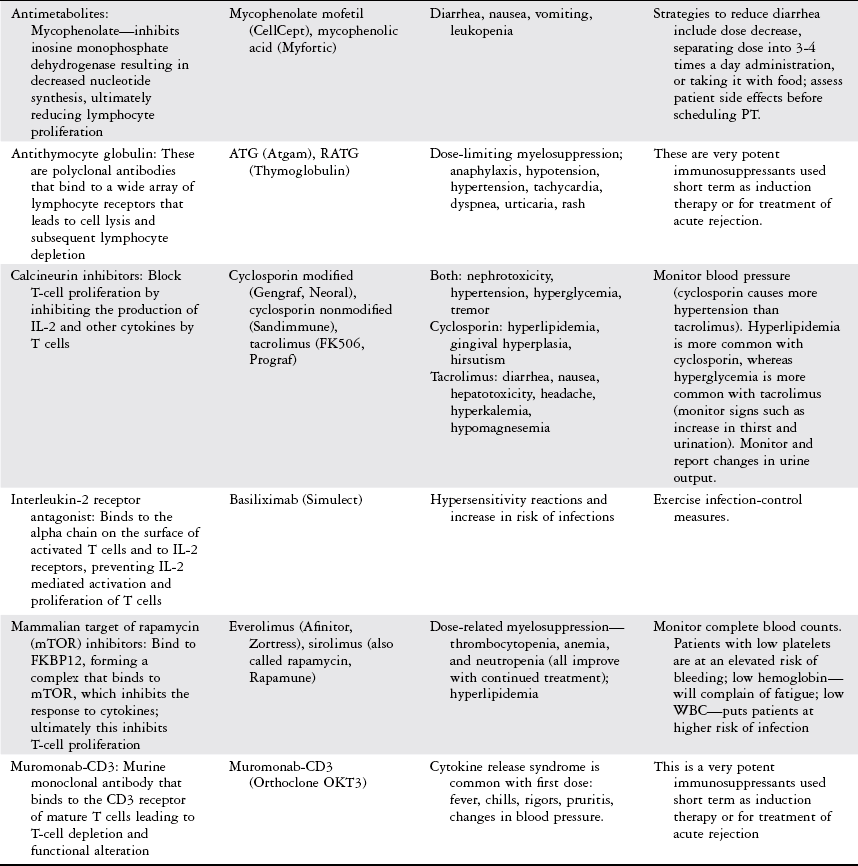

Cutaneous stimulation techniques include:. Provide pharmacologic pain management as ordered. Pain management using pharmacologic methods involves using opioids narcotics , nonopioids NSAIDs , and coanalgesic drugs. The World Health Organization WHO in published guidelines in the logical usage of analgesics to treat cancer using a three-step ladder approach — also known as the analgesic ladder. Self-reporting is not always reliable, however, and should not be taken at face value but rather should be viewed as just one component of the overall assessment used to support findings. Unidimensional self-report measures are the most widely used because they are simple to administer, valid, reliable, and easily understood by diverse populations, including children, adolescents, older adults, and those with communication deficits.

These may or may not be devised using a unidimensional scale. The PROMIS multidimensional scale has become widely used as a comprehensive, standardized, reliable, and valid measure of many of the multidimensional constructs of chronic pain presented above. However, this tool is long and complicated, and not usually feasible in a clinical setting. Another subset of chronic pain assessment tools employs standardized, objective behavioral observation methods to assess controllable and uncontrollable pain behaviors in the chronic pain patient.

These types of tools are typically used in research but have been useful in clinical work to help quantify chronic pain and to gain further understanding of the potential pain reinforcers that exist in the environment. Behavioral observation methods are generally effective with non-communicative, illiterate, or cognitively impaired patients, where direct observation provides the most objective approach to assessing pain behavior.

Direct observation can consist of a standardized task or occur in a natural setting. Proxy or surrogate reports from family members and caregivers can provide a wealth of information about chronic pain that is experienced by the individual sufferer who is unable to communicate through self-report. Lastly, there are emerging assessment techniques such as genetic testing and brain neuroimaging that can help to provide a full picture of what the patient is experiencing.

A comprehensive list currently available pain evaluation scales may be found in Fillingim, et al ; 4 Turk, et al, 5 and Arbuck, et al. In addition to the technical challenges of pain assessment, there is an ethical challenge: the assumption is that the chronic pain sufferer or their proxy is capable of reliably and objectively communicating about their pain. Since chronic pain has been deemed a subjective, personal, and private experience, there may be difficulties in objectively measuring it with self-report or observational tools alone.

Nathanial Katz. Additionally, there are some cases where patients may have be drug-seeking, facing addiction, or suffering from malingering , which raises concern for the clinician. Many of the self-report tools are face-valid, resulting in an easier ability to falsify reports. Other factors affecting self- and proxy-based reports have to do with how the patient or caregiver conceptualizes pain and the questions they ask. Responses may be influenced by pain severity, circumstance eg, movement, inertia , or medication need at the time of answering a questionnaire.

One study concluded that fewer than half of the practitioners from a sample of primary care clinicians working with chronic pain patients were apt to use chronic pain assessments to help guide treatment decisions. Reasons for this consisted of a lack of knowledge of effective measures, lack of time, and preference to just talk to their patients. Other standardized tools may seem too exhausting and time-consuming to use, such as the PROMIS tool as noted, which was developed for research purposes.

Recent research suggests that the ideal assessment and treatment of chronic pain conditions comes from an interdisciplinary approach incorporating simultaneous assessment and treatment of a chronic pain patient by multiple specialists. Pain is one of the top reasons for patients to see a physician in the office. In a pediatric primary care setting, Grout and colleagues found that pain was reported by the patient or caregiver in The same condition should not be treated in disconnect, it being pneumonia, heart disease, or pain.

Clark and Galati suggested that practitioners become comfortable with a few valid and reliable measurements relevant to their patient population. For instance, a minimum requirement for chronic pain assessment in back pain patients in one study included assessment in pain intensity, pain duration, affect, and pain disability. Predetermined scales used in clinical practice should be easy to understand, time-efficient, flexible for a patient or a caregiver to learn quickly and intuitively, as wide in scope as possible, inexpensive, and based on principles already familiar to the patients. The assessments can be used throughout the course of treatment to help assess the effectiveness of treatment, changes in pain, and account for other psychosocial factors that may influence chronic pain, which could flag those patients who may require further evaluation by specialists.

The IPCPS has the ability to quickly assess pain intensity over time and captures how pain interferes with function and the relationship between pain, depression, and anxiety. Some of the measures are administered at each appointment, even if a patient comes daily or weekly, allowing frequent assessment of pain intensity, location, temporal changes, and psychosocial factors that ultimately create a dialogue between patient and clinician and identify effective treatment planning that is patient specific.

This type of extensive evaluation likely cannot be achieved without the involvement of a behavioral health professional; however, identifying a local behavioral health professional for further consultation is workable for smaller clinics or for those who need to refer out. This battery typically takes individuals with an 8 th grade reading level approximately 10 to 15 minutes to complete. When creating the IPCPS, the developers took into account a hectic, fast-paced clinical practice and a diverse patient population. They took the basics of a VAS and combined it with both numerical and verbal descriptors to create a unique rating system. One unique feature of the IPCPS scale is that it allows patients to report two values of pain at the same time:. Allowing a patient the ability to use these scales flexibly generates practical conversations between practitioner and patient.

Practical scales like the IPCPS allow a clinician to have a better understanding of the scope of the chronic pain affecting a patient, and ultimately those factors amplifying the pain experience and possible disability. With this fuller assessment, treatment decisions may be made with more confidence. As stated, neglecting the psychosocial and behavioral aspects of chronic pain could lead to inaccurate diagnosis and ineffective treatment as chronic pain cannot be determined solely by a biomedical assessment. Such a rigid approach could maintain the suffering reported by chronic pain patients, increase healthcare utilization, and contribute to rising healthcare costs.

Further, bare-bones assessment strategies may increase the risk of leaning toward the use of treating pain intensity by opioid-based therapies alone without adjunctive treatments. As the scientific understanding of pain evolves, additional evaluation tools are destined to be created. While scans, sophisticated labs, and biomedical tests will continue to advance, self-report scales used to assess the multifaceted nature of chronic pain will not disappear. The best chronic pain assessments, therefore, must be clinically useful and not simply research responsive. Such tools need to be practical in the hands of both general clinicians as well as specialists, user friendly, and convenient to use both digitally and on paper. Ideally, they will help to distinguish between acute and chronic pain and guide effective treatment to improve the life of the pain sufferer.

While this achievement is still ahead of us but, with a biopsychosocial approach, we will be moving in the right direction. Assessment of patients with chronic pain.

Various Acute Pain Assessment treatment options should be explained including rationale for therapies. Development of Acute Pain Assessment Neck Pain and Disability Wild Geese Mary Oliver Analysis. Paracetamol is specifically recommended first-line for management of strains and sprains [15].